Introduction

It is not uncommon in the contemporary world for a city to have a gay villages or “gaybourhood”. Paris has “Le Marais”, New York has the “Village”. Gay villages are an urban phenomenon where large amounts of LGBTQ+ orientated businesses and residences have been established, forming an oasis of safety in an otherwise hostile city space. Like many other urbanised minority spaces, these “villages” reflect certain cultural values of the community and cater to the particular needs of the community in relation to wider society.

Many sources accept that LGBTQ+ areas within cities are important for both LGBTQ+ people of all ages and their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts. Within this research, London’s Soho is frequently used as a case study, being one of the most mainstream and profitable gay villages in the world. Situated in the heart of central London, Soho is notorious for its nightlife, shopping, and dining. It has been a particular area of scrutiny with many LGBTQ+ Urban researchers devoting parts of their research to understanding and explaining its urban characteristics.

However, with the majority of research on gay villages (and specifically Soho) being at least a decade old, I wonder whether today’s youth, given changing attitudes within the LGBTQ+ community towards identity and sense of self, still feel like Soho is a relevant space for themselves?

London is a constantly changing city with tight regulations on what can and cannot be built and demolished. Tracing historical sources, Soho has changed multiple times over the last 200 years. Soho has never been formally or administratively bound, although like most of London there is a general consensus of place and local identity. For the purposes of my research, I am focusing on Old Compton Street and its surroundings as the predominant area of LGBTQ+ activity in the otherwise loosely defined region. Soho is not the only area in London that is associated with London’s LGBTQ+ diaspora, but it is definitely the most notorious and most central. As a result, and considering recent trends of LGBTQ+ venue closure, its relevance to LGBTQ+ youth is important.

There is no universally accepted definition of youth. For the purposes of my research, I will be focusing on those above the legal drinking age, 18 years old, up to 24, following the United Nations who define a youth as someone between the ages of 15 and 24.1

The title of this essay comes from my interview with Sylvester, a quip that summarises my questions and captures the casual attitude of youth I am dealing with.

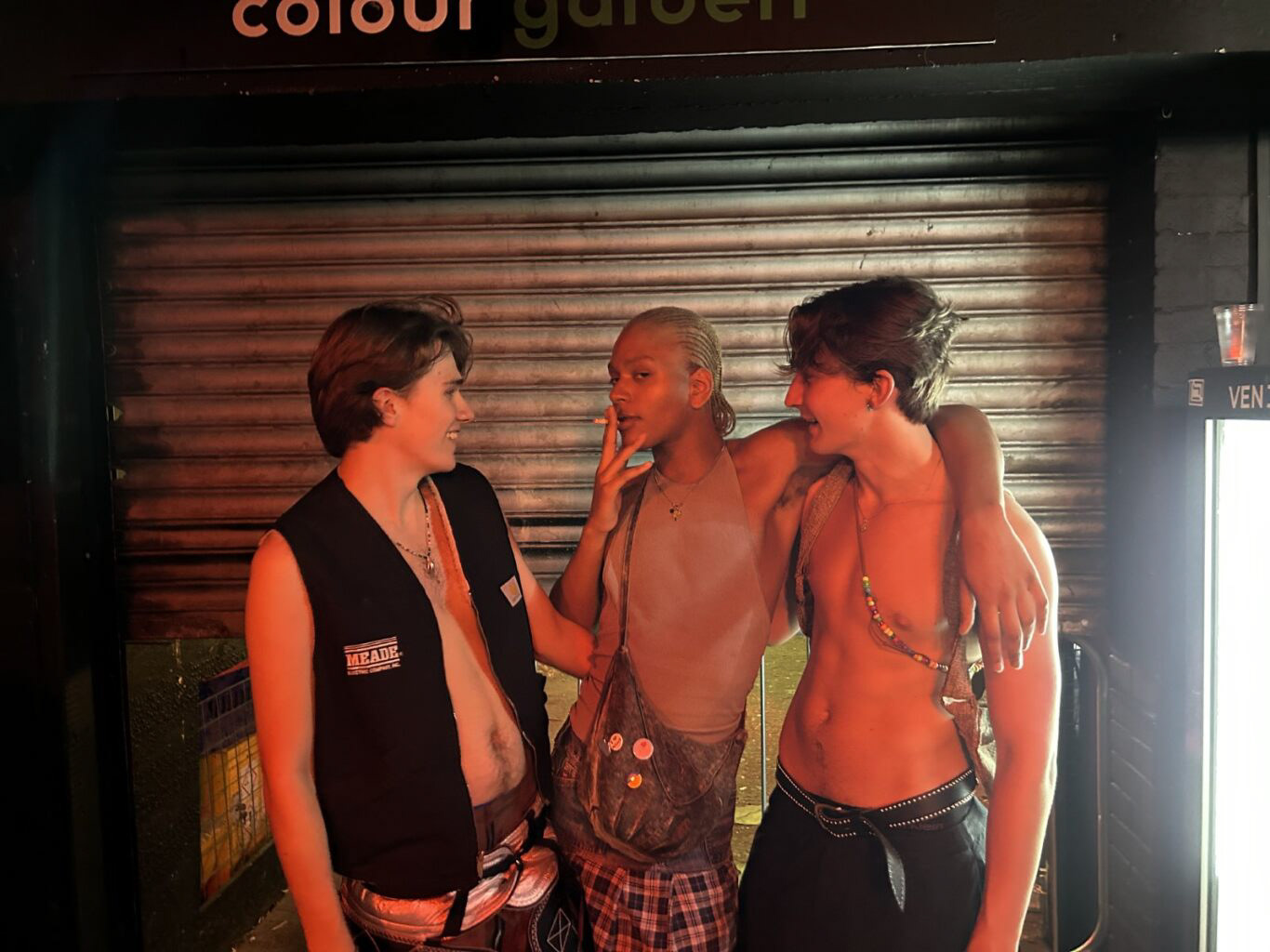

Fig.1 - Myself and friends at on a gay night out 15/07/2023 - Taken by a friend.

Soho's Original Adult Store, taken by Author, 2024

Sign outside Coptons, Taken By Author, 2024

Map Of Soho's Boundaries

Methodology

To understand if and why attitudes have changed, I will be exploring Soho’s contemporary history and the systems in place, both administrative and social, which control how gay villages grow and decline in relevancy. I will do this firstly by analysing key literature exploring themes of sexual tourism, homonormativity and venue closures. This exploration will also be ethnographic, considering my own prolonged observations of Soho and the experiences of other young Londoners, which I have obtained through interview. A frequent visitor of Soho myself, I conducted multiple studies of Old Compton Street throughout December 2023 and January 2024, with an aim to better understand the rhythms and aesthetics of Soho. I walked down the street, browsed at shops, drank at bars and talked to strangers in the smoking areas. Whilst I acknowledge the benefits of my whiteness and Cis-ness in my assimilation into Soho’s general culture, I believe my experience to be a fair representation of at least surface-level Soho life, if not a deeper picture of the day-to-day rhythms of the streets. I have had to make educated assumptions based on my own experiences which I believe to give an unbiased picture of Soho’s scene.

Over my research period, I undertook a series of 6 interviews. Albeit a small pool with potentially limited scope, I conducted a holistic interview style with the interviewees to authentically capture a fully personalised response to Soho, which I could then use to validate some of my own experiences and also highlight disparities between the way we treated the space and were treated by it. Combining it with academic papers, journalism, and social media, I believe this allows me to create a fair picture of Soho through human experience. All ethics guidelines will be followed to protect the identities of the interviewees.

Over my research period, I undertook a series of 6 interviews. Albeit a small pool with potentially limited scope, I conducted a holistic interview style with the interviewees to authentically capture a fully personalised response to Soho, which I could then use to validate some of my own experiences and also highlight disparities between the way we treated the space and were treated by it. Combining it with academic papers, journalism, and social media, I believe this allows me to create a fair picture of Soho through human experience. All ethics guidelines will be followed to protect the identities of the interviewees.

“The Dilly’s not what it used to be”

Whilst areas, such as Soho, which have become prominent neighbourhoods in their own right, have only emerged as LGBTQ+ destinations within the last 50 years, “lesbian and gay spaces” have existed for a long time. Invisible networks of queer space have always existed throughout the heterosexual city, formed by public cruising areas or secret bars and, in London, can be traced back as far as the 17th century2. Bars are and have been incubatory space for political movements and can provide space where expectations of the outside world are reversed.

Until the 17th Century, the land now occupied by Soho was a hunting ground3. After the Great Fire of London had left approximately 100,000 homeless in London4, Soho was one of many periphery districts that were settled in. The area was distinctly working class, compared to its neighbour Mayfair, on the other side of Regent Street. However it was not until the spread of Asiatic Cholera in 1854 that the idea of Soho as a slum was permanently fixed in popular imagination. Soho and the nearby Piccadilly were popular with the sex industry from the 18th century5. This included male prostitutes, known as the Dilly Boys. Dilly boys were attractive, young and camp in order to attract punters. Homosexuality was present on the streets if you looked for it. Notable Sohoite, Quentin Crisp recalls passing through the west end: “as I wandered along Piccadilly or Shaftesbury Avenue, I passed young men standing at the street corners who said, “Isn’t it terrible tonight, dear? No men about. The Dilly’s not what it used to be”. These ‘Dilly Boys’ were the epitome of the gay ‘dandy’ scene, sought out for their youth6.

Until the 17th Century, the land now occupied by Soho was a hunting ground3. After the Great Fire of London had left approximately 100,000 homeless in London4, Soho was one of many periphery districts that were settled in. The area was distinctly working class, compared to its neighbour Mayfair, on the other side of Regent Street. However it was not until the spread of Asiatic Cholera in 1854 that the idea of Soho as a slum was permanently fixed in popular imagination. Soho and the nearby Piccadilly were popular with the sex industry from the 18th century5. This included male prostitutes, known as the Dilly Boys. Dilly boys were attractive, young and camp in order to attract punters. Homosexuality was present on the streets if you looked for it. Notable Sohoite, Quentin Crisp recalls passing through the west end: “as I wandered along Piccadilly or Shaftesbury Avenue, I passed young men standing at the street corners who said, “Isn’t it terrible tonight, dear? No men about. The Dilly’s not what it used to be”. These ‘Dilly Boys’ were the epitome of the gay ‘dandy’ scene, sought out for their youth6.

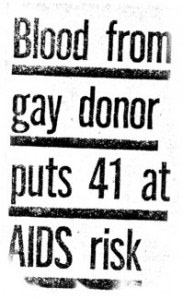

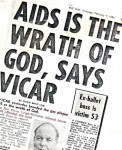

The sex industry thrived in Soho until the 1980s, however, was also met with challenges. AIDS, which was initially identified as a Gay cancer or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID), was seen to be connected to the sexual liberation of the decades before. Furthermore, the media was pushing an agenda of loathing that sustained the idea that gay men themselves were the cause of the epidemic.7 This agenda of loathing was further bolstered by the Thatcher Government’s passing of the infamous Section 28, which prevented local authorities from promoting homosexuality as pretended family relationships.

Francis ‘The Horse’ Kane 1983, Male prostitute

New Soho

The challenges that faced the LGBTQ+ community also brought them closer together. On the 20th February 1988 20,000 people protested against Section 28 in Manchester and 30,000 did the same in June at the London Gay Pride march.8 AIDS had also made homosexuality more visible than ever before, with organisations such as ACT-UP London (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) being set up following the US example. Soho as we know it today was seen to be born out of this newfound community.

The urban transformation of the area began as local establishments begun to cater to gay men (some already had, albeit unofficially eg. The Admiral Duncan, Comptons, etc.)9 Bell & Binnie credit the opening of the Village Soho, in 1991, at the western corner of Old Compton Street as the establishment that revolutionised Soho.10 Fitted with glass windows at street level, this was the first bar in the area that did not hide its interior activities. Throughout the following decade over 30 new openly-gay bars opened with a similar style to that of the village11, mostly based around Old Compton Street (e.g. Ku bar, Freedom etc. This business-led growth was unique to Soho in the UK. (Manchester’s gay village was supported and funded by the local council, Soho received no aid from Westminster City Council). Alan Collins notes that this is unlike the neighbouring Chinatown, which relied on significant formal attention from the Conservative-run council authority, who installed cctv in the area and pedestrianised it.12 Soho’s growth also coincided with legal changes in the UK. The age of consent changed for homosexuals in 1994 to 18 and in 2001 to 16. Civil partnerships were introduced in 2004 and the 2005 Adoption Act permitted unmarried (and same-sex) couples to adopt children.13 Collins studied Soho’s growth through an economic lens. Soho has been and is a primarily commercial area, with very little housing. Soho has had success with both homosexual and heterosexual consumers. Collins notes that in Black et al.’s 2002 US census, the data indicates that gay men are disproportionately observed to live in areas with high numbers of amenity locations.14 (In fact, he goes as far to suggest that the presence of amenities is a more convincing predictor of gay location choice than “gay friendliness”). Collins also suggests that UK LGBTQ+ culture is “too heavily reliant on high amenity-focused consumption”.

This is only a brief overview of Soho’s former ties with homosexuality and sex in general, however, despite its conciseness, it is plain to see that the area and its clientele have all been shaped by sexuality, whether positive or negative (e.g. the lack of help from council) however these changes tended to happen around key events in LGBTQ+ liberation and equality.

The urban transformation of the area began as local establishments begun to cater to gay men (some already had, albeit unofficially eg. The Admiral Duncan, Comptons, etc.)9 Bell & Binnie credit the opening of the Village Soho, in 1991, at the western corner of Old Compton Street as the establishment that revolutionised Soho.10 Fitted with glass windows at street level, this was the first bar in the area that did not hide its interior activities. Throughout the following decade over 30 new openly-gay bars opened with a similar style to that of the village11, mostly based around Old Compton Street (e.g. Ku bar, Freedom etc. This business-led growth was unique to Soho in the UK. (Manchester’s gay village was supported and funded by the local council, Soho received no aid from Westminster City Council). Alan Collins notes that this is unlike the neighbouring Chinatown, which relied on significant formal attention from the Conservative-run council authority, who installed cctv in the area and pedestrianised it.12 Soho’s growth also coincided with legal changes in the UK. The age of consent changed for homosexuals in 1994 to 18 and in 2001 to 16. Civil partnerships were introduced in 2004 and the 2005 Adoption Act permitted unmarried (and same-sex) couples to adopt children.13 Collins studied Soho’s growth through an economic lens. Soho has been and is a primarily commercial area, with very little housing. Soho has had success with both homosexual and heterosexual consumers. Collins notes that in Black et al.’s 2002 US census, the data indicates that gay men are disproportionately observed to live in areas with high numbers of amenity locations.14 (In fact, he goes as far to suggest that the presence of amenities is a more convincing predictor of gay location choice than “gay friendliness”). Collins also suggests that UK LGBTQ+ culture is “too heavily reliant on high amenity-focused consumption”.

This is only a brief overview of Soho’s former ties with homosexuality and sex in general, however, despite its conciseness, it is plain to see that the area and its clientele have all been shaped by sexuality, whether positive or negative (e.g. the lack of help from council) however these changes tended to happen around key events in LGBTQ+ liberation and equality.

The writing from Soho’s heyday represents contemporary mindsets on Soho’s success but falls short of its future. The writings describe why Soho has developed but not the effects its consumeristic growth has in the othering of deviant members of the community.

Collins did map out the stages of development of the urban gay villages of England. (Fig.11). In his study, he predicts that there will come a time when some gay villages will even have a declining phase, but for him, this is only a prediction as at the time there was no proof.

Collins did map out the stages of development of the urban gay villages of England. (Fig.11). In his study, he predicts that there will come a time when some gay villages will even have a declining phase, but for him, this is only a prediction as at the time there was no proof.

Protests against Section 28 in 1988. -Mathew Hodson

Demonstration promoting human rights for peoplw with aids- 1988 Image - Matthew Hodson

Homonormativity

The word “homonormativity” is thrown around a lot with regards to the evolution of LGBTQ+ aesthetics and is particularly crucial when analysing Soho’s streets and their visual signals. The term homonormativity was coined by Lisa Duggan in 2003 in her critique of contemporary LGBTQ+ culture.16 Readers may be more familiar with the term heteronormativity, which is the idea of heterosexuality and cisgenderism as the dominant culture, an assumed “normal”. Homonormativity is the appropriation of such heteronormative ideals onto LGBTQ+ identities and culture, creating a sort of normalised politics of LGBTQ+ expression and culturally specific way of (particularly) being gay or lesbian that is both palatable and in sync with these existing heteronormative norms. These homonormative ideals particularly began to infiltrate Soho post-AIDS crisis, when a banalisation of gay and lesbian politics was happening.17 Johan Andersson argues that this was in part a reaction to the problematic reputations of the lesbian and gay communities during the AIDS crisis. There was, post-AIDS, a cleaning up of the gay image and as Duggan states a replacement of “public visibility” with a “privatised depoliticised gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption”.18

Homonormativity was a main sculpting factor in Soho’s major changes. The ideals of homonormativity extended from just a human scale but also to an urban scale. Soho began to represent a particular breed of LGBTQ+ consumer, being that of the upper-class white gay man. In-line the cleaner, fitter and so-called “respectable” image of the yuppie gay man came the hygienic modernism of Soho’s bars. As well as putting gay clientele on display, the glass windows of Village Soho and Rupert St were easy to clean and sanitise.19 There was a transition from older, darker leather bars towards chic, not just in Soho, but London-wide. Modernism was an architectural tabula rasa for Soho; the old, queer and camp were rejected as “too much”.20 Only the palatable gay man was marketable. This phenomenon was not just linked to the built environment but also printed media. Ultimately this is down to the money as Dereka Rushbrook says “Gay urban spectacles attract tourists and investment; sexually deviant, dangerous rather than merely risqué, landscapes do not”.21 These writings acknowledge the reasons why Soho looks the way it does but do not extend beyond the aesthetics. Andersson writes about how Soho became unwelcoming to those who lay outside the aesthetic but does not delve into those who are experiencing Soho for the first time but those who grew up during the AIDS epidemic.

As Soho grew in popularity with its homosexual client base so did it with another. As sexual diversity comes further into the mainstream, so does the spectalisation of the LGBTQ+ community. Events such as Pride become citywide events, attended by mayors and residents alike. In the same way visitors may visit London’s Chinatown to eat more authentic eastern food, Soho has become a tourist destination not only for shopping but breathing in a more tolerant air.

Sexual Tourism

Dereka Rushbrook notes that “queer bodies provide a chic stamp of approval”.22 Sexual diversity highlights a venue’s sophistication and is therefore encouraged by those who wish to market and commodify space to outsiders. This commodification of LGBTQ+ space often neglects other subcategories such as race, gender and class and pushes those forgotten others towards peripheral spaces instead. As a result, it is predominantly white middle and upper-class gays and their heterosexual counterparts who aid this sexual gentrification of cities. For example, in San Fransisco, the gay scene had a reputation for permitting ““homosexuals (to continue) to socialise publically alongside adventurous heterosexuals and voyeuristic tourists”.23 Collins states that mature urban gay villages have thrived to such an extent that they are “chic social and cultural centres of the city” and the “place to be seen” regardless of one’s sexual preferences. These spaces no longer only provide safety for their intended clientele. Canal Street in Manchester is known not just as a LGBTQ+ haven but also a safe zone for heterosexual women.24 In London, Clayton Littlewood, former Old Compton Street business owner described Soho as a “modern day Hogarth painting” where all sorts of people could interact.25 Rushbrook’s writing is applicable to the UK, from the US examples she writes about. This increasing consumption of LGBTQ+ space by those who do not identify as part of the community has led to concerns over the authenticity of Soho.

Heaven nightclub advertising on instagram.

The Slow Death of Soho

Venue closure has been a hot topic in London’s LGBTQ+ media in the past decade. The Guardian splashes titles like “The Slow Death of Soho”26 and the Economist runs articles such as “So Long, Soho”. 27

Campkin and Marshall’s 2016 and 2017 surveys on behalf of their research for UCL’s Urban Lab provide detailed data to help piece together a clearer representation of Soho’s changing scene.28 Surveying 239 people, the study illustrates a vivid picture of attitudes to LGBTQ+ venues. The most shocking statistic (although perhaps unsurprising to London’s LGBTQ+ community) is that since 2006, the number of LGBTQ+ venues in London has dropped from 121 to 51, a net decrease of 58%. Compared with general UK trends of venue closure, there is a clear disproportionate heightened drop in LGBTQ+ venues. The high percentage of venue closures related to redevelopment is significant as we must consider the relatively small numbers of such venues in the first place.

There are also numerous disparities in the planning system which allow such venues to disappear. In the 1980’s the abolition of Light Industrial Use as a separate class (Use Classes Order 1987) meant that property developers could replace light industrial spaces with offices without having to apply for a change of use from the council. Craftsmen, tailors and small businesses were pushed out of the area as they were not as profitable as office workers.29

In the 2000s the advent of Crossrail (now the Elizabeth Line) heavily affected Soho’s gay businesses. Campkin analyses the effects of this new urban infrastructure in his book, Queer Premises.30

Using the Closure of the Astoria in 2008 as a case study (as well as that of First Out, in the St. Giles area), Campkin analyses the watering down of LGBTQ+ importance in the screening and planning processes and criticises the profit-driven GLA for not understanding the “of the function or social value of an LGB venue, nor why the GLA might be concerned about the loss of such an establishment”. For Crossrail developers the site was a “valuable addition and strategic acquisition”.31 Despite an initial equalities impact screening, the Astoria was demolished, with backing from Mayor Ken Livingstone.32

Using multiple case studies Campkin describes the high amount of venue closure due to Crossrail. Even after its opening, local LGBTQ+ venues are struggling as their LGBTQ+ neighbours disappear. While writing this essay, Jeremy Joseph, owner of the G-A-Y brand, announced via Instagram that G-A-Y Late , Heaven’s smaller, more central counterpart would be closing on the 10th of December 2023.33 The venue was a two-minute walk away from the new Tottenham Court Road station. Joseph claimed that keeping the venue open was a “losing battle” and that the lack of surrounding LGBTQ+ venues meant that it was impossible to guarantee customer safety once they left the club. He also attacked the increasing amount of building works around the area and the underfunding of local police forces.

Campkin and Marshall’s 2016 and 2017 surveys on behalf of their research for UCL’s Urban Lab provide detailed data to help piece together a clearer representation of Soho’s changing scene.28 Surveying 239 people, the study illustrates a vivid picture of attitudes to LGBTQ+ venues. The most shocking statistic (although perhaps unsurprising to London’s LGBTQ+ community) is that since 2006, the number of LGBTQ+ venues in London has dropped from 121 to 51, a net decrease of 58%. Compared with general UK trends of venue closure, there is a clear disproportionate heightened drop in LGBTQ+ venues. The high percentage of venue closures related to redevelopment is significant as we must consider the relatively small numbers of such venues in the first place.

There are also numerous disparities in the planning system which allow such venues to disappear. In the 1980’s the abolition of Light Industrial Use as a separate class (Use Classes Order 1987) meant that property developers could replace light industrial spaces with offices without having to apply for a change of use from the council. Craftsmen, tailors and small businesses were pushed out of the area as they were not as profitable as office workers.29

In the 2000s the advent of Crossrail (now the Elizabeth Line) heavily affected Soho’s gay businesses. Campkin analyses the effects of this new urban infrastructure in his book, Queer Premises.30

Using the Closure of the Astoria in 2008 as a case study (as well as that of First Out, in the St. Giles area), Campkin analyses the watering down of LGBTQ+ importance in the screening and planning processes and criticises the profit-driven GLA for not understanding the “of the function or social value of an LGB venue, nor why the GLA might be concerned about the loss of such an establishment”. For Crossrail developers the site was a “valuable addition and strategic acquisition”.31 Despite an initial equalities impact screening, the Astoria was demolished, with backing from Mayor Ken Livingstone.32

Using multiple case studies Campkin describes the high amount of venue closure due to Crossrail. Even after its opening, local LGBTQ+ venues are struggling as their LGBTQ+ neighbours disappear. While writing this essay, Jeremy Joseph, owner of the G-A-Y brand, announced via Instagram that G-A-Y Late , Heaven’s smaller, more central counterpart would be closing on the 10th of December 2023.33 The venue was a two-minute walk away from the new Tottenham Court Road station. Joseph claimed that keeping the venue open was a “losing battle” and that the lack of surrounding LGBTQ+ venues meant that it was impossible to guarantee customer safety once they left the club. He also attacked the increasing amount of building works around the area and the underfunding of local police forces.

Venturi, Campkin and Marshall all highlight the disparity in the system: that community value is overshadowed by profit when it comes to planning. The “pink pound” mentioned by researchers at the turn of the century still was in play in the 2010s and 20s. The writings begin to understand how this affects everyday consumers, stopping short of youth, who as a result of these closures, inherit a very different Soho from their elders. There is clearly a lack of adequate protection for LGBTQ+ businesses from the negative impacts of new developments.

- Homophobic press articles circa. 1985

Jeremy Joseph’s statement on the closure of G-A-Y Late (via Instagram)

Collin’s Table of the stages of urban gaybourhood development

ETHNOGRAPHY

Ethnography

There is no one overall experience of Soho. Everyone’s experiences are highly nuanced, and impacted by a range of factors including gender, sexuality, age and body shape. I’ve divided my ethnographic research into three themes: Nostalgia, accessibility and changing cultures. Before I delve into my experience, I would like to address the discomfort I felt in taking photographs along Old Compton Street. Despite my comfort within Soho’s streets, I felt by taking my camera out, I was prying on Soho’s safety and invading the privacy of the bargoers. I therefore tried to avoid taking photographs of anyone’s faces. Even though it was not my intention, I felt like I was contributing towards the spectalisation of the LGBTQ+ lifestyles present on the street. All photographs used in this essay were used with consent from the individuals in them, but whether all of these photographs should have been taken in the first place, I am not sure.

Moor Street - Taken by Author

Photographs of the ‘Bear Bar’ in both day and night. Photographs by author

Photographs of the ‘Bear Bar’ in both day and night. Photographs by author

Nostalgia

Approaching from Moor St, during the daylight, and having made one’s journey past the bustle of theatre-goers and tourists, one is greeted with the semi-pedestrianised gay haven that is Old Compton Street. Apart from the occasional taxi, the road is completely traffic-free. No busses pass through the Soho area. Amin Ghaziani, in his book “There Goes the Gaybourhood” makes the point that where we “choose to live (and spend time and money) is a personal and intimate decision”. 34 What matters is where we feel comfortable to do so, driven by personal experience. There does not seem to be a particular youthful draw towards the area in the daytime. Many bars are closed, and it is perhaps too early to justify stopping off in any of the pubs. Many of the shops that are open, such as Sunspel and J W Anderson have few customers. Sylvester works on Old Compton Street in a designer menswear shop. He describes the clientele as: “more arty than other streets, lots of tourists, I guess there were more gay people, more gay customers… Does the store fit into Soho? Kind of yes and no, it’s kinda gross, so commercial now”.

Perceptions and rumours affect our choices of where we spend time. Alexandra told me that her “first time out in London was always going to be in Soho” as she had seen so much about it online. She wanted to be surrounded by other people like herself. Sylvester said that his own parents had, during his childhood, always told him “it was cool” that he had his hair cut in Soho and that it was a “really cool place”. He would love to have a Time Machine to see “how it was”. There is definitely a sense of Soho’s past importance on its streets and yet it is hard to find exactly where that LGBTQ+ draw is . With this in mind, newer bars on Greek Street such as Club 59 and Louche “don’t seem gay”. A major concern shared amongst my interviewees was venue closure and venue transformation away from LGBTQ+ havens to generic, “straight-friendly” bars. The proliferation of straight people in Soho’s bars and streets has slowly changed the character of these spaces. This diluting of an already small pool of spaces means that “authentic” LGBTQ+ experiences are far and few between.

Ultimately Soho’s bars have a reputation amongst my interviewees for always being an option for a night out. Set establishments have consistency to their weekly nights and when there are no options, Soho is remembered as reliable, no matter how “uncool” it seems.

Perceptions and rumours affect our choices of where we spend time. Alexandra told me that her “first time out in London was always going to be in Soho” as she had seen so much about it online. She wanted to be surrounded by other people like herself. Sylvester said that his own parents had, during his childhood, always told him “it was cool” that he had his hair cut in Soho and that it was a “really cool place”. He would love to have a Time Machine to see “how it was”. There is definitely a sense of Soho’s past importance on its streets and yet it is hard to find exactly where that LGBTQ+ draw is . With this in mind, newer bars on Greek Street such as Club 59 and Louche “don’t seem gay”. A major concern shared amongst my interviewees was venue closure and venue transformation away from LGBTQ+ havens to generic, “straight-friendly” bars. The proliferation of straight people in Soho’s bars and streets has slowly changed the character of these spaces. This diluting of an already small pool of spaces means that “authentic” LGBTQ+ experiences are far and few between.

Ultimately Soho’s bars have a reputation amongst my interviewees for always being an option for a night out. Set establishments have consistency to their weekly nights and when there are no options, Soho is remembered as reliable, no matter how “uncool” it seems.

Map of Old Compton Street provided by Sylvester 17/02/2024

Accessibility

Soho’s contemporary aesthetics don’t reflect my interviewees nor their friends. Simon described the bars as “polarising” with a “marmite effect”. You either feel “totally affirmed” just by walking through the door or like a “total freak”. Olivia, who is heterosexual, said that she felt safer in gay bars. She could dance without fear of harassment and the music was more often to her taste. Others, such as Alexandra highlighted discomfort, both on the street and in venues, citing both racism and transphobia on the nightclub door that had been experienced by her friends. Soho is seen as synonymous with a drinking and drug culture. Half of the interviewees had taken drugs when in Soho. Many stressed how this made nighttime unsafe, particularly for women on their own. If going out with friends, Alexandra would meet them outside Soho, so that she wouldn’t have to enter the area alone. Queer women in particular were highlighted as a group that Soho did not provide for or look after. There is only one lesbian bar on Old Compton Street, She-Bar. Malaysia also stressed that even in queer-orientated spaces, she often could not be sure “who was a safe person” due to the high volume of heterosexual women in the spaces.

From my own observations, the nighttime street crowd are a mix of ages, with more adult-looking men and women than youths. Unlike daytime, where I’ve noticed that most people are simple passing through Soho, now the street is filled with its actual users. To estimate, the crowd is mostly between 25-40 and predominantly white and male. There are some women, but noticeably few expressing any intimacy, unlike the men, who are not afraid to hold hands or kiss in the streets.

In her interview Alexandra, pointed out gaps within LGBTQ+ venues. “My friends don’t want to go out in central (London), they’re not white and they don’t want to go to Heaven”. She also reiterates a rumour that I myself had also heard thrown around, in Freshers and also online “Heaven doesn’t let people in because they don’t look gay”. Campkin and Marshall discovered a similar perception in their surveys; that there was a dearth of “provision of LGBTQ+ venues or spaces serving women, trans, non-binary and Queer, Trans and Intersex People of Colour (QTIPOC) communities.” 36

Soho seems LGBTQ+ coded because of its clientele, not because of the built infrastructure. Pride flags draped over the walls do not make me, nor my interviewees resonate with a particular space more than a regular bar. Some chains use rainbows in their branding (such as Nando’s) to show that they are the Soho version. I am sure that the Soho Nando’s is no queerer than any other across the country. With that said, Malaysia pointed out that a pride flag over the door can just be an affirming sign that this space is for “us and not the straights”. She also pointed out that both me and her were lucky enough to not need a pride flag or safe space to be our whole selves as queer people. For some, the heterosexual tyranny of their household means that gay bars and the gaybourhood in general provide much-needed freedom from heteronormativity. All my interviewees expressed a dislike of Heaven and G-A-Y and yet most spend their first-ever club nights in those specific venues. There is a privilege amongst some of London’s LGBTQ+ youth, in that they can reject these Soho spaces; in 2024 sexuality is no longer reliant on them. Malaysia described going to heaven as a “queer rite-of-passage” and yet says she would not go back now. For many, non-Londoners, who’s hometowns may not even have a club, let alone a LGBTQ+ one, this is a privilege they do not have. This rejection of central LGBTQ+ nightlife also prompts exploration of the wider city. This wider exploration has proven to my interviewees that in fact, Soho is perhaps no longer the most important gaybourhood in London. Simon prefers Clapham for a “gay night out” and Lucinda would choose “Canning Town over Soho every time”. Lucinda wanted Soho to “Be less pretentious!”. She did not understand ‘Why should you have to act a certain way or dress a certain way’. Out of all the interviewees, she felt the most uncomfortable in the space. This was due both to bad experiences but also because she could not find a space she resonated with in Soho. This lack of resonance seems to be what keeps young LGBTQ+ people from coming back to Soho. It is seen as a space for “older gays”.

Soho seems LGBTQ+ coded because of its clientele, not because of the built infrastructure. Pride flags draped over the walls do not make me, nor my interviewees resonate with a particular space more than a regular bar. Some chains use rainbows in their branding (such as Nando’s) to show that they are the Soho version. I am sure that the Soho Nando’s is no queerer than any other across the country. With that said, Malaysia pointed out that a pride flag over the door can just be an affirming sign that this space is for “us and not the straights”. She also pointed out that both me and her were lucky enough to not need a pride flag or safe space to be our whole selves as queer people. For some, the heterosexual tyranny of their household means that gay bars and the gaybourhood in general provide much-needed freedom from heteronormativity. All my interviewees expressed a dislike of Heaven and G-A-Y and yet most spend their first-ever club nights in those specific venues. There is a privilege amongst some of London’s LGBTQ+ youth, in that they can reject these Soho spaces; in 2024 sexuality is no longer reliant on them. Malaysia described going to heaven as a “queer rite-of-passage” and yet says she would not go back now. For many, non-Londoners, who’s hometowns may not even have a club, let alone a LGBTQ+ one, this is a privilege they do not have. This rejection of central LGBTQ+ nightlife also prompts exploration of the wider city. This wider exploration has proven to my interviewees that in fact, Soho is perhaps no longer the most important gaybourhood in London. Simon prefers Clapham for a “gay night out” and Lucinda would choose “Canning Town over Soho every time”. Lucinda wanted Soho to “Be less pretentious!”. She did not understand ‘Why should you have to act a certain way or dress a certain way’. Out of all the interviewees, she felt the most uncomfortable in the space. This was due both to bad experiences but also because she could not find a space she resonated with in Soho. This lack of resonance seems to be what keeps young LGBTQ+ people from coming back to Soho. It is seen as a space for “older gays”.

Gay Nandos, Taken by Author, 2024

Prowler, Taken by Author, 2024

Homophobic protester during London Pride, taken By Author 2023

Changing Community

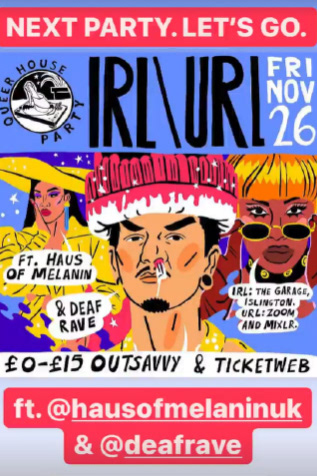

The way that LGBTQ+ people view and define their community has changed. Gay neighbourhoods are not the foundation of gay communities anymore. Interviewees mentioned a plethora of digital LGBTQ+ resources that helped them feel more connected to other LGBTQ+ people than Soho did. Queer House Party, an online club event started during the pandemic, was mentioned multiple times.36 A safe digital space allows connection across the country not just in London.

Interviewees were divided over the increasing mainstreaming and consumerism of the LGBTQ+ community. Two-thirds of interviewees felt that London Pride was too corporate. A “gay marketing campaign”, it was seen as out of touch with the general LGBTQ+ population, despite some “incredible” charity work that happened alongside, such as the Terence Higgins Trust. It is often hard to tell whether corporations like M&S and Unilever are supporting LGBTQ+ people or just cashing

Interviewees were divided over the increasing mainstreaming and consumerism of the LGBTQ+ community. Two-thirds of interviewees felt that London Pride was too corporate. A “gay marketing campaign”, it was seen as out of touch with the general LGBTQ+ population, despite some “incredible” charity work that happened alongside, such as the Terence Higgins Trust. It is often hard to tell whether corporations like M&S and Unilever are supporting LGBTQ+ people or just cashing

in on an economic opportunity. In Soho particularly (compared with London as a whole), Pride was also seen as not doing enough to destigmatise the homonormative images of the community. My experience of Soho during Pride is that it is especially white, fit, older, and male.

There is a perceived sense of who is more welcome in this space and who should stay well clear. I have found myself comparing myself to other sohoites, thinking I should look like them in order to be accepted by the community. Heading into the shops, these ideas of who is desirable and who isn’t are again reinforced by the images on the products. Magazines featuring mainly young men feature heavily in the displays and posters of (mainly white) men in tight-fitting jock straps and sex costumes highlighting their chiseled bodies, cover the walls. This clean and fit aesthetic ties in with the 90s image of the metrosexual gay man, the one that Soho thrived around. Today, my interviewees connect with these images less. Social media promotes other expressions of gayness and queerness. To me, these shops are out of touch with the gay scene outside of Soho.

Queer House Party Poster 2020

Queer House Party Poster 2020

Sex Shop on Berwick Street, Taken by Author, 2024

Photo from Heaven's Instagram

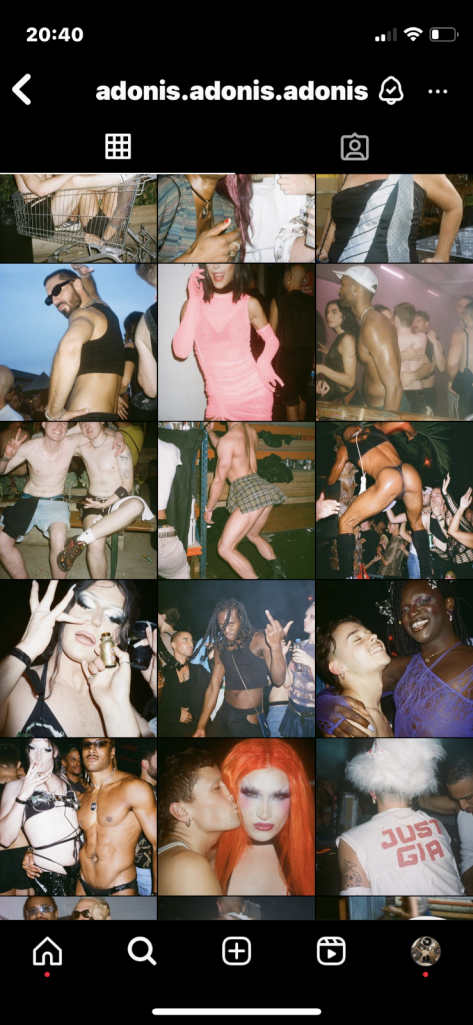

There is also a perceived shift away from sexual orientation defining one’s sense of self in 2024, when compared to the 90s and 2000s. Simon felt some spaces “didn’t give their people pride”, rather were just “relics” of Soho’s heyday. He acknowledged that these spaces were vital post-AIDS and that community gatherings provided a space for gay consciousness to flourish but nowadays this consciousness is present in a wider spread of the city. East London, particularly around Dalston, Hackney, and Canning Town was highlighted as a newly-queer area, providing for queer individuals “what Soho did for gay men” in the 90s and 2000s. The scene in East London is also seen as less fixed on specific bars and clubs but rather on event nights. Alexandra said that she was a regular at events such as 2cperriera, Inferno, and Riposte. These events are not as frequent but are, as a result, more special to the community when they do happen. These events rarely take place in Soho, where venue hire is too expensive.37

Another event that Alexandra mentioned was Pxssy Palace. Pxssy Palace went viral within right-wing media in 2022 for their entry policy which charges non-minorities was over 6 times more than their minority counterparts.38 The aim is to reduce the number of customers who are not a part of their target audience. Alexandra says: ‘This may seem intense but so often within gay and lesbian space the “pink premium” that affords total safety within LGBTQ+ space is only afforded to white cis consumers… I’m not saying this is the best policy ever or could be a citywide thing to keep spaces safe, but it is certainly not a terrible idea…(otherwise) Soho’s scene is too exclusive”.

Another event that Alexandra mentioned was Pxssy Palace. Pxssy Palace went viral within right-wing media in 2022 for their entry policy which charges non-minorities was over 6 times more than their minority counterparts.38 The aim is to reduce the number of customers who are not a part of their target audience. Alexandra says: ‘This may seem intense but so often within gay and lesbian space the “pink premium” that affords total safety within LGBTQ+ space is only afforded to white cis consumers… I’m not saying this is the best policy ever or could be a citywide thing to keep spaces safe, but it is certainly not a terrible idea…(otherwise) Soho’s scene is too exclusive”.

At the end of the day, the white cisgendered LGBTQ+ community, including myself, need to think what our own complicity is in the culture of difference and othering of the rest of the community. Most interviewees acknowledged that a lot of white gay and lesbian activism was limited in its scope, stepping around topics such as race or class, naturalising queerness as both white and middle class in the same way seen in Soho’s homonormative development in the 90s. This bolsters the inaccessibility to non-conformers and sexual others.

Finally, Malaysia mourned the recent closure of G-A-Y Late. “I’ve heard so much about places closing down but I think this is the first time I’ve really felt the impacts of it…like that’s a bar that I go to”. Young people may not resonate so much with venue closures like the Astoria or First Out, simply because they were unable to go in the first place. 24-year-olds were only of legal drinking age in 2018 and the Coronavirus pandemic in 2020 put nightlife on standstill for 2 years. The relevance of these closures seems to only be hitting for the first time now that G-A-Y Late is closing, whether loved or hated.

Conclusion

The community that benefitted the most and drove the capital of 90s and 2000s Soho will ironically herald its death. The increased visibility and consumption of a particular brand of gay man also threatens to in its ignorance of sexual deviance in consumed space to make Soho irrelevant to today’s youth. The perceived desexing and depoliticising of gay and lesbian spaces may make the spaces accessible, on the surface level, to the general population, but also removes the history of grit and radical bravery that fought for the right for these spaces to exist. To the young, the mainstreaming of Soho, allows them to eventually reject the space in search of wider more accessible LGBTQ+ space. A welcoming embrace into the community perhaps gives enough of a platform for White Cis youth to find and orientate themselves within the heteronormative city but does not provide this hospitality to those who deviate from the wider tolerated image of a metrosexual gay man. I do not doubt that Soho will continue to be popular with heterosexual tourists but as it uses homosexuality to attract a heterosexual market, it misses an opportunity to radically redefine public urban opinion of the wider LGBTQ+ community and provide safety and comfort to them. As a result, Soho has fallen out of favour with and is no longer relevant to most LGBTQ+ youth.

nferno (based in Hackney) manifesto.

Contrasting Instagrams of Heaven (Soho) and Adonis (based in Canning Town)

Contrasting Instagrams of Heaven (Soho) and Adonis (based in Canning Town)

She-Bar Soho (2024) Taken by author

Anonymous submission, two young people doing Cocaine in Soho.

The sign outside of Comptons. (2024) Taken by author

Soho’s Original Adult Store (2024) - Taken by Author

1. “Youth,” United Nations, accessed February 19, 2024

2. “A Short History of the British Gay Bar,” VICE, May 17, 2017,

3. Summers, 1989

4. “The Great Fire of London 1666 Collection,” Museum of London, July 28, 2022,

5. Venturi, 2018

6. Crisp, 1985

7. Colin Clews, “1984-85. Media: AIDS and the British Press - Gay in the 80s,” Gay in the 80s - A personal account of LGBT life in the 1980s in the UK, USA and Australia, November 6, 2019,

3. Summers, 1989

4. “The Great Fire of London 1666 Collection,” Museum of London, July 28, 2022,

5. Venturi, 2018

6. Crisp, 1985

7. Colin Clews, “1984-85. Media: AIDS and the British Press - Gay in the 80s,” Gay in the 80s - A personal account of LGBT life in the 1980s in the UK, USA and Australia, November 6, 2019,

8. Venturi, 2018

9. Bell & Binnie, 2004

10. Ibid

11. Venturi, 2018

12. Collins, 2004

13. Ibid

14. Ibid

9. Bell & Binnie, 2004

10. Ibid

11. Venturi, 2018

12. Collins, 2004

13. Ibid

14. Ibid

15. Collins, 2004

16. Duggan, 2002

17. Andersson, 2018

18. Duggan, 2002

19. Forty, 1986

20. Andersson 2018

16. Duggan, 2002

17. Andersson, 2018

18. Duggan, 2002

19. Forty, 1986

20. Andersson 2018

21. Rushbrook, 2002

22. Ibid

22. Alamilla Boyd, 1997

23. Collins, 2004

24. Clayton, 2005

22. Ibid

22. Alamilla Boyd, 1997

23. Collins, 2004

24. Clayton, 2005

26. The Guardian, 2014

27. The Economist, 2014

28. Campkin & Marshall, 2017

29. Venturi, 2018

30. Campkin, 2023

31. John Burns quoted in Pink News, 2006

32. Hoyle, 2010

33. Joseph (via Instagram), 2023

27. The Economist, 2014

28. Campkin & Marshall, 2017

29. Venturi, 2018

30. Campkin, 2023

31. John Burns quoted in Pink News, 2006

32. Hoyle, 2010

33. Joseph (via Instagram), 2023

34. Ghaziani, 2014

35. Campkin & Marshall, 201736

36“Queer House Party Facebook,” Facebook,2024

37. The Independant, 2023

38. The Daily Mail, 2022

38. The Daily Mail, 2022

Bibliography

Andersson, Johan. “Homonormative Aesthetics: AIDS and ‘de-Generational Unremembering’ in 1990s London.” Urban Studies 56, no. 14 (December 18, 2018): 2993–3010. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018806149.

Bell, David, and Jon Binnie. “Authenticating Queer Space: Citizenship, Urbanism and Governance.” Urban Studies 41, no. 9 (August 2004): 1807–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000243165.

Campkin, Ben, and Lo Marshall. “LGBTQ+ Cultural Infrastructure in London: Night Venues, 2006–Present .” UCL Urban Laboratory, 2017.

Campkin, Ben, and Lo Marshall. “LGBTQ+ Cultural Infrastructure in London: Night Venues, 2006–Present .” UCL Urban Laboratory, 2017.

Binnie, J. (1995) ‘Trading Places: Consumption, Sexuality and the Production of Queer Space’ in Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, edited by D. Bell and G. Valentine. London: Routledge, pp. 182-99.

Campkin, Ben. Queer premises: LGBTQ+ venues in London since the 1980s. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.

Clayton, A. (2005) Decadent London: Fin de Siècle City. London: Historical Publications Ltd.

Collins, Alan. “Sexual Dissidence, Enterprise and Assimilation: Bedfellows in Urban Regeneration.” Urban Studies 41, no. 9 (August 2004): 1789–1806. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000243156.

Crisp, Q. (1985) The Naked Civil Servant. London: Flamingo.

Crisp, Q. (1985) The Naked Civil Servant. London: Flamingo.

Duggan, Lisa. “The New Homonormativity.” Materializing Democracy, 2002, 175–94. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822383901-007.

Duggan, Lisa. The twilight of equality? neoliberalism, cultural politics, and the attack on democracy. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004.

Forty A (1986) Objects of Desire: Design and Society since 1750. London: Thames and Hudson.

Ghaziani, Amin. There goes the Gayborhood?, August 10, 2014. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691158792.001.0001.

Ghaziani, Amin. There goes the Gayborhood?, August 10, 2014. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691158792.001.0001.

Hoyle, Ben. “‘smelly’ Astoria Makes Way for Crossrail.” The Times & The Sunday Times: April 3, 2010. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/smelly-astoria-makes-way-for-crossrail-5672sd5kppg.

Houghton, Elizabeth. “Becoming a Neoliberal Subject.” Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organisation 19, no. 3 (2019): 615–26.

Mort, Frank. “Social and Symbolic Fathers and Sons in Postwar Britain.” Journal of British Studies 38, no. 3 (July 1999): 353–84. https://doi.org/10.1086/386198.

Munoz, José Esteban. Cruising utopia: The then and there of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Nan Alamilla Boyd, “‘Homos Invade S.F.!’: San Francisco’s History as a Wide-Open Town, in Beemyn, Creating a Place for Ourselves, 73–95, 1997

Rushbrook, Dereka. “Cities, Queer Space, and the Cosmopolitan Tourist.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 8, no. 1–2 (April 1, 2002): 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-8-1-2-183.

Somerville, Siobhan B. “52 Queer.” Keywords for American Cultural Studies, Second Edition, December 31, 2020, 203–7. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814708491.003.0057.

Summers, J. (1989) Soho: A History of London’s most Colourful Neighbourhood. London: Bloomsbury

Venturi, Marco. “Out of Soho, Back into the Closet: Re-Thinking the London Gay Community,” 2018.

“Youth.” United Nations. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth#:~:text=Who%20Are%20the%20Youth%3F,of%2015%20and%2024%20years.

“A Short History of the British Gay Bar.” VICE, May 17, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en/article/53n4px/a-short-history-of-the-british-gay-bar.

Museum of London. “The Great Fire of London 1666 Collection.” Museum of London, July 28, 2022. https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/great-fire-london-1666#:~:text=The%20Great%20Fire%20of%20London%20is%20one%20of%20the%20most,Farriner%27s%20bakery%20on%20Pudding%20Lane.

Clews, Colin. “1984-85. Media: AIDS and the British Press - Gay in the 80s.” Gay in the 80s - A personal account of LGBT life in the 1980s in the UK, USA and Australia, November 6, 2019. https://www.gayinthe80s.com/2013/01/1984-85-media-aids-and-the-british-press/.

“The Slow Death of Soho: Farewell to London’s Sleazy Heartland.” The Guardian, November 25, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/nov/25/the-slow-death-of-soho-farewell-to-londons-sleazy-heartland.

“Queer House Party Facebook.” Facebook. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.facebook.com/queerhouseparty/.

“So Long, Soho.” The Economist, 2014. https://www.economist.com/britain/2014/12/30/so-long-soho.

Marc Shoffmann, ‘Petition Launched to Save Gay Club’, Pink News, 24 August 2006a, https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2006/08/24/petition-launched-to-save-gay-club/

Marc Shoffmann, ‘Petition Launched to Save Gay Club’, Pink News, 24 August 2006a, https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2006/08/24/petition-launched-to-save-gay-club/

Department for Transport, Crossrail Equality Impact Assessment: Public Consultation Comments and Crossrail’s Response (London: Department for Transport, January 2008),

“Jeremy Joseph on Instagram:” Instagram. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C0Cc2EJILmE/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA.

“Renting London Office Space Now £1,000 per Desk - Study Reveals Most Expensive Areas.” The Independent, September 14, 2023. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/london-renting-offices-expensive-uk-b2411497.html.

John Abiona For The Daily Mail. “Party at Club Is Blasted over £112 ‘man Tax’ That Charged Straight Males up to Six Times More for Entry than Other Guests.” Daily Mail Online, January 31, 2022. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10462283/Party-club-blasted-112-man-tax-t.html.